MAXIM KANTOR: SELECTIONS FROM THE "WASTELAND" AND "METROPOLIS" PRINT SUITS

October 18 - November 23 at the University of Notre Dame's Snite Museum of Art

ARTICLES ABOUT THE SHOW:

|

MAXIM KANTOR X-RAYS MORAL AND POLITICS IN HISTORY

In fall 2008, a new Russian comedy was performed with great success in Moscow. Whoever looked at the program could find that the stage decorations had been done by a person with the same name as the author of the comedy. But the identity of the names is not accidental – the writer and the painter are the same person. |

|---|

Maxim Kantor is indeed one of the most astonishing persons in the contemporary arts. His paintings and drawings have fascinated private collectors as well as some of the greatest museums of the world for now more than two decades. Yet in 2006, he published a two-volume novel The Drawing Textbook that became an instant success in Russia and was quickly compared by reviewers to Tolstoy's War and Peace . It is the greatest novelistic representation of the collapse of the Soviet Union and its aftermath, doubtless the most momentous historical event of the decades following World War II. In late 2007, a volume with eight comedies followed, some of which were, as just mentioned, represented for the first time in 2008. Kantor's move to literature is amazing, since there have been only few persons in history who were both great painters and writers. What is the reason for this change? It would be completely wrong to interpret Kantor's switch to literature as a sign of a postmodern desire to erase all borders and give up all continuity. On the contrary, there are few persons so much convinced of the basic difference between right and wrong and of the necessity of a generating principle for an artist's style as Maxim Kantor is. And in fact it is not difficult to interpret both his figurative and his literary works as two attempts to express with different aesthetic tools the same truths. As awestricken as one is by the range of Kantor's talents, it is obvious why this artist could become a writer. His art was from the beginning committed to content, to a moral evaluation of politics, to an interpretation of historical transitions.

In the history of aesthetics, we find both thinkers who defend the complete autonomy of the form and others who measure the form by a moral content it seeks to express. While most of the figurative art of the 20 th century has been spellbound by the predominant formalism, Kantor from his first paintings revolted against what he perceived as its emptiness. Forms have to signify something relevant in order to be legitimate. Thus, Kantor does not simply return to some type of expressionist realism. More and more his paintings and drawings have an allegorical besides their “literary” meaning, as he himself tells us in the introduction to one of his catalogues. From the beginning, Kazimir Malevich's famous Black Square was the type of art Kantor rejected, but in his great cycle Metropolis , we find red squares, standing on one of their edges: Kantor integrates Malevich in his own aesthetic universe by, first, changing the color into its polar opposite and, second, giving it a meaning. What is its meaning? Well, the red square stands – for Kantor himself, the anti-Malevich. In the earlier cycle Wasteland , the red parts, achieved by the technique of woodcut, represent the Asian moment of Russian culture; at the same time they point to deeper strata, which only the artist can access. Thus, Maxim Kantor in Brothers is depicted as having red glasses that penetrate reality, as in one of his oil paintings he is the blind man seeing, surrounded by dogs that symbolize the elementary force of life. In the background of Brothers , one sees his aging fathers, the famous art historian Karl Kantor, slowly moving on crutches and throwing a red shadow, in which he is transformed into an angel. Indeed, it is the artistic education that Karl gave Maxim that made his extraordinary work possible.

Kantor's work can be thoroughly enjoyed only by those who are familiar with the history of art. As every literary text is full of intertextual allusions, so great art is inevitably “inter-iconic”, as one might say. But in an age so aware of history as ours, the explicit allusions to the past can achieve a density unknown in earlier epochs – at least if the artist is as educated as Kantor is. That his art is influenced by German expressionism, is visible at first glance; but it is important to look a second or a third time at his drawings and paintings to understand how subtly Kantor transforms and develops expressionism. In Fish-eaters , for example, the fish-devouring caricatures seem to stem from George Grosz. But let us look again at the face of the man on the left: It is composed of smaller units, like in the paintings of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, the great 16 th century painter. However, it is not fruits or vegetables that constitute this face – it is testicles! This explicit sexualization of Arcimboldo points back into the 20 th century, but the object in the center of the painting builds on a millennial symbolic tradition. The fish is the Christian symbol; and that only a skeleton has remained of it, is a powerful expression of the forces that are corroding the Christian message in our time.

Clearly, many of the works by Kantor are satiric attacks against society – this is true of his figurative art as well as of his literary work. His great self-portrait with the maliciously observing, almost threatening eyes, the mouth closed to a narrow line, and his brush reminiscent of a rapier that can hit at any moment is an appropriate self-interpretation of the artist. It is tempting to connect this vitriolic attitude with the moral chaos that ensued in the 1990es after the collapse of the Soviet Union and its dominant ideology, Marxism. This collapse almost inevitably engendered a widespread feeling that people had been deceived and that now everybody was justified in pursuing his own interest in the most reckless way. It is tempting, but it would be utterly misleading nevertheless. For Kantor's satiric force is rooted, like that of the ancient Roman satirists, in a most rigorous moral vision of the universe. Kantor is not a cynic, he is a moralist, and he is proud of being a moralist in a “moralophobic” time like ours. Kantor's intelligent moralism implies undergoing risks. The same man who in the 1980s had to work in the underground because Soviet totalitarianism did not allow this relentless critic of The Red House (this is the title of one of the most powerful allegoric paintings of Soviet power) to pursue an official career as artist, in the 1990s depicted with accusing despair the transformation of his fatherland into a homeland of the most vulgar predatory capitalists on the one hand and pauperized millions on the other. Look at Open Society : Very few and modest commodities remain on sale for the poorest of the poor, who even have to struggle for their acquisition. This painting is more powerful than whole libraries written against unbounded neoliberalism. At the same time, the three beggars in the world of blue cold that constitutes the painting with this title have a dignity alien to the new elites of post-Soviet Russia.

Not satisfied with his criticism of contemporary Russia , in Metropolis Kantor attacks the globalized world that seemed to emerge from the “triumph” of the new American empire. He indeed sits between all chairs, as he paints himself in one of his wittiest paintings, in which the absurdity of the situation reminds us of Rene Magritte, while the shoes of the artist indicate that he is no less than Vincent van Gogh's heir. What are the reasons for Kantor's discontent with the “victory” of the new style of life? The paintings “Dirty Bed Cloths” and “Newspaper” contain part of the answer. The modern world is utterly indifferent to differences of rank: Information of the most different origin and value is mixed together, we see artifacts of modern technology, frogmen fighting terrorism, religious and political dignitaries. Under the inviting headline “Enjoy global world” we can admire a head offered on a plate. Needless to say, this reminds us of Saint John the Baptist and of the price that the construction of an empire signifies for its victims, be it the Roman or the American empire. The pomegranates that surround it are old symbols of death: They tied Persephone to the Netherworld. But they make out of this part of the painting something like a still life, even if at the same Kantor mocks the genre: It is not venison that is exposed, but a human head. Upon it treads a naked woman, an easily recognizable quote from Amedeo Modigliani. She is stepping towards a man who looks out of the barred window of a prison. Quick sex and quick learning, a voyeuristic attitude towards human suffering, the loss of the religious valence of age-old icons, all these appear as characteristics of the modern predicament. At the same time the painting is full of religious symbols, like the angels that announce the impending judgment with their trumpets. It is not clear whether they are part of the trivialized postmodern worldview, or whether they are the force that is supposed to challenge it. In any case, they have to be distinguished from the ecclesiastic leaders. In Metropolis , one of the most impressive drawings presents the contrast between Saint Augustine and Saint Francis, between the bishop in his power and pomp and the stigmatized wretch. It is the capacity to recognize the divine in the poorest victims of society that in Kantor's eyes constitutes the essence of Christianity. In Requiem for a terrorist , the corpse disposed of by persons whom we have at least as much reason to fear as the terrorists themselves reminds the spectator of the deposition from the cross. This is provocative, as is a crucifixion painted by Kantor with Christ completely naked. But is it a provocation authorized by the Gospel itself. Like in the case of Tolstoy, whom Kantor portrays leaving his home in 1910, the Russian painter's reservations with regard to ecclesiastical hierarchy is compatible with a continuous inspiration by the morality of the Gospel and by Christian iconography.

Kantor has contributed so much to the interpretation of the current world that he has every right occasionally to portray himself and explain his understanding of his own art. The graphic where we see him in the position of Saint Luke, painting the Virgin and the child with its fingers raised to form the ‘Victory' sign, is particularly illuminating: The canvas within the drawing contains a Pieta, an aged Virgin with her dead son. This is what true art does – it does not simply mirror or reproduce reality (what would be the use of that?), but it transforms it. It renders it perhaps more ugly, but by doing so points to essential truths. Babel Tower is certainly one of Kantor's most powerful attempts to give an interpretation of human history. Pieter Bruegel's “Little” Tower of Babel (in the Museum Boymans-van Beuningen in Rotterdam, to be distinguished from the better known Tower of Babel in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna) is the model, but what does Kantor make out of it! The aborted tower is transformed into a rocket and ends in modern skyscrapers. It thus becomes a powerful symbol of how modern technology is in itself as megalomaniac and doomed to fail as that ancient building about which Genesis 11 tells us its story. Paul Klee's watercolor Angelus Novus was famously interpreted by Walter Benjamin as representing the angel of history, driven away by the horrors that history continues to pile up. Kantor's Babel Tower in its different variations, as well as the whole of his work, will help generations to come to make sense of history in general and of the last decades in particular as very few other artworks of our time are able to do.

|

POLITICS POWER RUSSIAN PRINTS By EVAN GILLESPIE, Tribune Correspondent On exhibit: SOUTH BEND: |

|---|

His 1,400-page political novel, “The Drawing Textbook,” sold a respectable number of copies in Russia and has been hailed by a few critics as the new “War and Peace.” An exhibition of Kantor's prints currently on display at the University of Notre Dame's Snite Museum of Art reveals the artist's visual work to be of the same super-sized, politically ambitious nature as his writing.

The show includes a fraction of two cycles of prints, “Wasteland” and “Metropolis,” both of which address the turmoil that enveloped Russia after the end of the Soviet Union at the close of the 20th century. Each of the two groups of 25 prints represents about only a third of the entirety of each suite, making these visual treatises the voluminous rival of the heftiest of Tolstoy novels. The prints circle the gallery on two levels, one suite above the other, and the dozens of images are packed with visual action and enough symbolism to keep a viewer, especially one well acquainted with Russian culture, busy for hours.

Despite the abundance of imagery, the show's themes are tightly presented and fairly easy to grasp: Russia as a nation in disarray, lacking a spiritual center, threatened by its desire to emulate the decadent West, in desperate need of a return to its Eastern roots for salvation.

The siren song of Western overindulgence is represented by an urban tower of Babel built on the bones of old Russia , and the moral tragedy of the citizenry shows up in an overcrowded apartment building, in which residents engage in all manner of depravity.

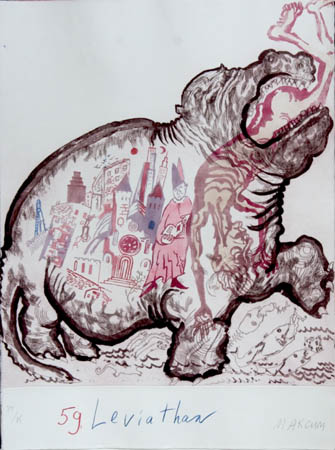

Mother Russia herself is the monster to be feared in another image, as she takes on the guise of Saturn, devouring her citizens the same way that the god consumed his own children (but here, Russia as Saturn is a rotund peasant rather than the ominous monster in Goya's famous painting of the same subject). In still other prints, terrorists menace and angels stand guard in a battle for the Russian soul.

Formally, Kantor's minimally colored prints borrow from German Expressionism, with a particular fondness for the grotesque imagery popular at the end of the 20th century. He combines etching with woodcut printing, the former representing the modern world, the latter looking back to the old style of lubok folk prints (a visual allusion used heavily by Russian Avant-Garde artists near the beginning of the 20th century). Color also is pressed into symbolic service, with red representing not only the old Soviet Union, but also the Eastern heart of Russian power.

Kantor creates a privileged place for himself in some of the images. In “Caught Between Two Stools,” he ponders whether he should settle in the painter's seat (an echo of Van Gogh's chair) or take up the stool upon which rests a book, presumably the throne of a writer. In “Saint Luke Draws the Virgin,” the saint is a self-portrait, the artist transforming the triumphant Madonna and Child into a mournful Pieta. Undoubtedly, Kantor sees himself as a conduit for large ideas about society and religion, and whether these ideas are expressed in words or pictures, they must be expressed, for the very future of Russia seems to depend on it.

This urban Tower of Babel in Maxim Kantor's “Metropolis” print series at the University of Notre Dame's Snite Museum of Art summarizes Kantor's depiction of post-Soviet Russia in the “Metropolis” and “Wasteland” series: Russia is a nation in disarray, lacking a spiritual center, threatened by its desire to emulate the decadent West, in desperate need of a return to its Eastern roots for salvation.